| TEST

| PURPOSE

| SCORE

|

SOCIAL ATTRACTION:

Place puppy in test area. From a few feet away the tester coaxes the pup to

her/him by clapping hands gently and kneeling down. Tester must coax in a direction

away from the point where it entered the testing area.

| Degree of social attraction, confidence or dependence.

| Came readily, tail up, jumped, bit at hands.(1)

Came readily, tail up, pawed, licked at hands.(2)

* Came readily, tail up.(3)

Came readily, tail down.(4)

Came hesitant, tail down.(5)

Didn't come at all.(6)

|

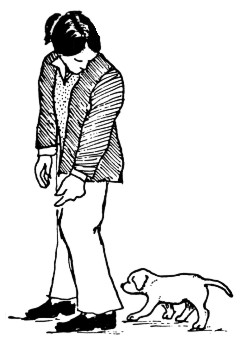

FOLLOWING:

Stand up and walk away from the pup in a normal manner. Make sure the pup sees

you walk away

| Degree of following attraction. Not following indicated

independence.

| Followed readily, tail up, got underfoot, bit at feet.(1)

Followed readily, tail up, got underfoot.(2)

* Followed readily, tail up.(3)

Followed readily, tail down.(4)

Followed hesitantly, tail down.(5)

No follow or went away.(6)

|

RESTRAINT:

Crouch down and gently roll the pup on his back and hold it with one hand for a

full 30 seconds.

| Degree of dominant or submissive tendency. How it

accepts stress, when socially/physically dominated.

| Struggled fiercely, flailed, bit.(1)

Struggled fiercely, flailed.(2)

* Settled, struggled, settled with some eye contact.(3)

Struggled then settled.(4)

No struggle.(5)

* No struggle, straining to avoid eye contact.(6)

|

SOCIAL DOMINANCE:

Let pup stand up and gently stroke him from the head to back while you crouch

beside him. Continue stroking until a recognizable behavior is established.

| Degree of acceptance of social dominance. Pup may try

to dominate by jumping and nipping or is independent and walks away.

| Jumped, pawed, bit, growled.(1)

Jumped, pawed.(2)

* Cuddles up to tester and tries to lick face.(3)

Squirmed, licked at hands.(4)

Rolled over, licked at hands.(5)

Went away and stayed away.(6)

|

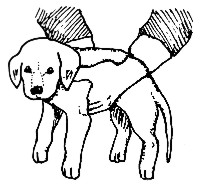

ELEVATION DOMINANCE:

Bend over and cradle the pup under its belly, fingers interlaced, palms up and

elevate it just off the ground. Hold it there for 30 seconds.

| Degree of accepting dominance while in position of no

control.

| Struggled fiercely, bit, growled.(1)

Struggled fiercely.(2)

* No struggle, relaxed.(3)

Struggled, settled, licked.(4)

No struggle, licked at hands.(5)

* No struggle, froze.(6)

| OBEDIENCE APTITUDE

| RETRIEVING:

Crouch beside pup and attract his attention with crumpled up paper ball.

When the pup shows interest and is watching, toss the object 4-6 feet in

front of pup.

| Degree of willingness to work with a human.

High correlation between ability to retrieve and successful guide dogs,

obedience dogs, field trial dogs.

| Chases object, picks up object and runs away.(1)

Chases object, stands over object does not return.(2)

Chases object and returns with object to tester.(3)

Chases object and returns without object to tester.(4)

Starts to chase object, loses interest.(5)

Does not chase object.(6)

| TOUCH SENSITIVITY:

Take puppy's webbing of one front foot and press between finger and thumb

lightly then more firmly till you get a response, while you count slowly to 10.

Stop as soon as puppy pulls away, or shows discomfort.

| Degree of sensitivity to touch.

| 8-10 counts before response.(1)

6-7 counts before response.(2)

5-6 counts before response.(3)

2-4 counts before response.(4)

1-2 counts before response.(5)

SOUND SENSITIVITY:

Place pup in the center of area, tester or assistant makes a sharp noise a few

feet from the puppy. A large metal spoon struck sharply on a metal pan twice

works well.

| Degree of sensitivity to sound. (Also can be a

rudimentary test for deafness).

| Listens, locates sound, walks towards it barking.(1)

Listens, locates sound, barks.(2)

Listens, locates sound, shows curiosity and walks toward sound.(3)

Listens, locates the sound.(4)

Cringes, backs off, hides.(5)

Ignores sound, shows no curiosity.(6)

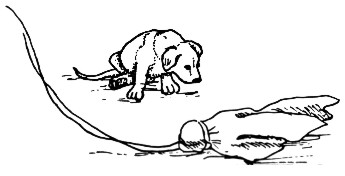

SIGHT SENSITIVITY:

Place pup in center of room. Tie a string around a large towel and jerk it

across the floor a few feet away from puppy.

| Degree of intelligent response to strange object.

| Looks, attacks and bites.(1)

Looks, barks and tail up.(2)

Looks curiously, attempts to investigate.(3)

Looks, barks, tail-tuck.(4)

Runs away, hides.(5)

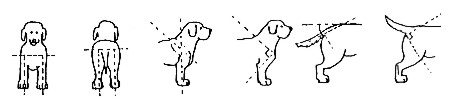

| STRUCTURE:

The puppy is gently set in a natural stance and evaluated for structure in the

following categories:

Straight front, Straight rear

Shoulder layback, Front angulation

Croup angulation, Rear angulation

(See Diagram Below)

Degree of structural soundness. Good structure is

necessary.

| The puppy is correct in structure.(good)

The puppy has a slight fault or deviation.(fair)

The puppy has extreme fault or deviation.(poor)

| | | | |

- Mostly 1's: This dog is extremely dominant and has aggressive tendencies. He is

quick to bite and is generally considered not good with children and elderly.

When combined with a 1 or 2 in touch sensitivity, will be a difficult dog to

train. Not a dog for the inexperienced handler; takes a competent trainer to

establish leadership.

- Mostly 2's: This dog is dominant and can be provoked to bite. Responds well to

firm, consistent, fair handling in an adult household, and is likely to be a

loyal pet once it respects its human leader. Often has bouncy, outgoing

temperament; may be too active for elderly, and too dominant for small children.

- Mostly 3's: This dog accepts humans as leaders easily. Is best prospect for the

average owner, adapts well to new situations and is generally good with children

and elderly, although may be inclined to be active. Makes a good obedience

prospect and usually has commonsense approach to life.

- Mostly 4's: This dog is submissive and will adapt to most households. May be

slightly less outgoing and active than a dog scoring mostly 3's. Gets along

well with children generally and trains well.

- Mostly 5's: This dog is extremely submissive and needs special handling to build

confidence and bring him out of his shell. Does not adapt well to change and

confusion and needs a very regular, structured environment. Usually safe around

children and bites only when severely stressed. Not a good choice for a

beginner since it frightens easily, and takes a long time to get used to new

experiences.

- Mostly 6's: This dog is independent. He is not affectionate and may dislike petting

and cuddling. It is difficult to establish a relationship with him whether for

working or for pet. Not recommended for children who may force attention on him;

he is not a beginner's dog.

- When combined with 1's, especially in restraint: the independent

dog is likely to bite under stress.

- When combine with 5's: the independent dog is likely to hide from people, or

freeze when approached by a stranger.

- No clear pattern: (several 1's, 2's, and 5's). This dog may not be feeling well.

Perhaps just ate or was recently wormed. Wait two days and retest. If the test

still shows wide variations (lots of 1's and 5's) he is probably unpredictable

and unlikely to be a good pet or obedience dog.

TIPS

- in social attraction and social dominance:

The socially attracted dog is more easily taught to come and is more cuddly and friendly.

Its interest in people can be a useful tool in training, despite other scores.

- in restraint and 1 in touch sensitivity:

The dominant aggressive dog, insensitive to touch will be a handful to train and

extremely difficult for anyone other than an exceptionally competent handler.

- instablity:

This is likely to be a "spooky" dog which is never desirable. It

requires a great deal of extra work to get a spooky dog adapted to new situations and

they generally can't be depended upon in a crisis.

- in touch and sound sensitivity:

May also be very "spooky" and needs delicate

handling to prevent the dog from becoming frightened.

After I understood the concepts involved in Puppy Aptitude Testing I was eager to observe it

first hand. Wendy invited me to accompany her when she tested a litter of ten

Newfoundland puppies. Two prospective buyers, who could not be present, had asked

Wendy to select puppies for them. Buyer A wanted a bouncy lively dog with good

conformation: a dog who would fit in with her two children and would be outgoing and

attract attention in the show ring. The buyer stated she could not stand a dog that

"hid under the table" when a family squabble occurred.

Buyer B, on the other hand, a quite, reserved person, wanted a companion with obedience

potential. He and his wife had no children and wanted a dog with a common sense

attitude that would adapt to quiet country life, but had the capability of working.

When I arrived, Wendy gathered up a handful of score sheets, ten colored pens, and ten

colored ribbons, a large metal pot, a large metal spoon, a roll of paper towels, a

bath towel, a ball of twine, a crumpled sheet of paper, a protractor, and a watch with

a second hand. She packed them into a paper bag and thrust it at me, saying, "You

will be in charge of recording and assisting." Leaving me no time to express my

inadequacies, we rushed off to the breeder. When we arrived, our ten unsuspecting

subjects were being cleaned off after splashing in the mud and they were lively and

ready for action.

The pups were 48 days old and were due to be sent off to their new homes on the weekend,

approximately their 51st day.

We decided that the breeder would bring the pups, one at a time, into the testing area (in

this case - the living room). I was to be in charge of tying a colored ribbon around

the puppy's neck and marking the score sheets in the same color. I took the paper sack

full of goodies and went to sit on the stairs where I would not distract the puppies

and had a good view of the action.

The breeder headed for the kennel and returned a few minutes later with a black female in

her arms. I tied an orange ribbon in a snug bow around her neck then the breeder

plunked her down in the doorway.

Wendy knelt down and attracted the puppy's attention by holding out her arms and saying

"puppy, puppy, puppy" in a friendly way. Little 'Orange' cocked her ears, galloped

over and attempted to lick Wendy's face. "Score that a 3, she came readily, tail up,

licked at face," said Wendy.

Wendy then stood up and walked away. Little Orange was fascinated by the pant legs and

yapped gleefully when she caught up to Wendy and tried to get in front. "Score that a

2, she followed readily, and got underfoot," said Wendy. "What's next "Restraint," I

said. "Get the watch with the second hand, and tell me when 30 seconds is up."

Wendy gently rolled little Orange onto her back and placed one hand on her chest. Little

Orange was not at all happy at this turn of events and said so emphatically. At the

same time she kicked and struggled fiercely and flailed the air with her feet, her

mouth open, trying to bite the hand the held her. Wendy had some trouble keeping the

pup on its back. "Time," I called out.

"Thank goodness! Definitely a 1, struggled fiercely, flailed, bit, what a fighter! Next?"

asked Wendy.

Social attraction was next, and the pup seemed to be getting her bearings while Wendy

stroked gently from head to tail. Wendy kept one hand cupped around the puppy's chest

lightly until a clear pattern was established. Little Orange decided that she enjoyed

petting and tried to lick Wendy's face. "Score that a 3, she cuddles and licks," said

Wendy.

Next Wendy gently cupped her hands underneath the puppy's rib cage and lifted her about ten

inches off the floor. Little Orange looked around but seemed relatively undisturbed.

"She's not at all tense or fearful, I'd score that a 3."

"Time for the obedience aptitude," said Wendy, "Hand me the crumpled paper." When I gave it

to her, Wendy squatted beside Little Orange and wiggled the paper in front of the puppy's

nose. When Little Orange began biting playfully at it, Wendy tossed it about four feet

away. Little Orange promptly pounced on it, picked it up and shook it. She then looked

at Wendy and galloped off in the opposite direction, which earned her a score of 1.

Wendy then collected the pup, lifted one of her front feet and gently pinched the skin

between the pup's toes; at first very lightly, then gradually bearing down until the

pup winced slightly and pulled her foot away. "It took about 7 counts, a little on the

insensitive side, I would say." I scored it a 2.

For the next test, sound sensitivity, I remained where I was, and clanked the metal spoon

against the pot, sharply. Little Orange looked up. At the next clank one could almost

hear her thinking, "What the devil was that noise?" as she cocked her ears and twisted

her head around. She did not, however, walk towards the sound. I scored her a 4.

Next I tied a six foot length of twine around the bath towel while Wendy distracted the

puppy with some cuddling. I placed the towel across the floor in front of them. Wendy

instructed me not to drag the towel towards the pup, since we did not want her to be

threatened, but simply to respond to a moving object. Little Orange watched with great

interest as the towel jerked across the floor then walked over and attempted to sniff

the towel. "Score that 3, attempts to investigate," said Wendy.

Finally Wendy evaluated the structure of Little Orange by placing her in a natural stance.

I found it difficult with my unpracticed eye to pick out the structural faults, but I

found that measuring of the angles of the shoulder and hips with a small protractor a

good way to check my guesses.

After all the fuss, Little Orange was given a couple of minutes of extra attention, was

taken back to the kennel and we proceeded to test the rest of the litter.

At the end of the testing (I was somewhat exhausted) we relaxed with a cup of coffee and

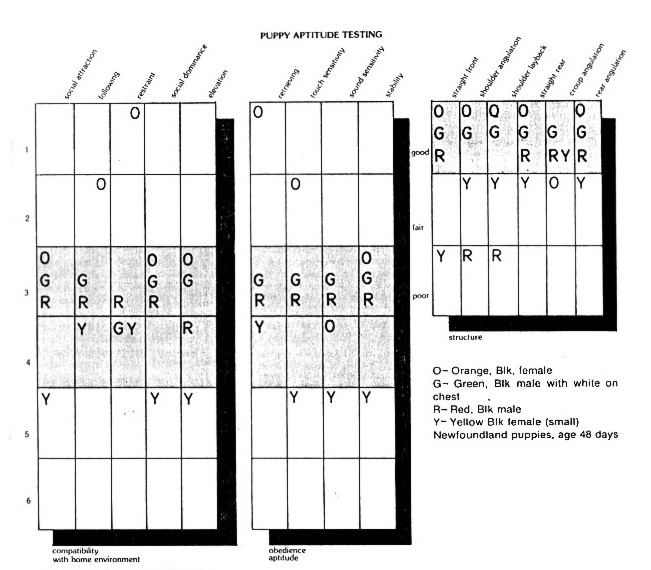

compared the scores of the puppies. Following is a chart comparing four of the puppies.

As you can see, Little Orange was the most dominant and scored above the shaded area

four times. Importantly, she was not fearful when faced by a strange situation, she

did not spook during the stability or sound test. Her scores indicate that she was

affectionate with people, something the would help to temper her tendency to touch

insensitivity and dominance.

Green on the other hand scored in the shaded area and was much less dominant the Orange and

more willing to accept human beings as leaders. Green showed excellent reactions to

retrieving, the stability and sound tests, and was medium sensitive to touch. In

addition, Green had excellent conformation.

Red was very similar to Green in scores but the straight shoulder structure predicts the

dog would have difficulty in standing up to the rigors of jumping required in advanced

competition.

Yellow's scores below the shaded area indicate that she was much more submissive than the

three others. In addition, she had a five on the stability test and scored as very

sensitive to sound and touch. Such a dog would be unlikely to do well in obedience

competition, and indeed may need special handling and a very supporting home.

Although Orange and Green both had good structure and were both "typey" specimens of their

breed, Orange's scores suggested should be a handful to train and that she did not have

the aptitude which Green had for obedience work. However, Orange's dominance and

excellent reaction to noisy, active situations, made her a likely candidate for Buyer

A's household and also for the breed ring. Green, on the other hand, went to Buyer B,

since she came closest to his requirements. Upon being questioned one year later both

buyers, (who, incidentally, own other dogs), stated that their respective dog met, in

fact exceeded, all their expectations.

In conclusion, I would like to say that I am grateful for having had an opportunity to

observe Puppy Aptitude Testing and I mean to present this article much in the same

manner as the Volhards presented it to me, not a gospel but as one way of matching

the right dog with the right owner.

With the soaring number of unwanted pets, I feel it is important to be able to select a

pet which is likely to fit the owners needs and adapt to complexities of modern life.

It is important for the prospective buyer to have a tool to recognize what he is seeing.

Most people would never dream of buying a car because "it was the nicest color" but many

people will buy a puppy because it "has the best markings." I shudder the think what

most parents would say if their daughter told them she would marry the first man to

walk up to her on the street, but they would think nothing of it if she picked a puppy

because it was the first out of the whelping box. This puppy may be the right

choice, then again, it may not, depending on what other traits make up its temperament.

Hopefully, the PAT will help the prospective buyer make a more educated choice.

The PAT can also be tailored to the needs of the breeder. In the case of the Volhards, the

aptitude tests were developed to show obedience potential. It would be easy enough to

test for aptitude in other areas such as field trial work, scent hound work, sheep

herding, (see Fox, 1975) and so forth. Testing puppies is certainly not a new idea --

Fortunate Fields in 1934, describes puppy tests for the working German Shephard Dog.

The breeder would use the information in the PAT not only to help determine which pup is the

most suited for which home but also to determine what temperament to select for. An

example might be a breeding of an extremely sensitive but very socially attracted bitch

with a medium sensitive but independent stud hoping for a medium sensitive puppies which

accepted leadership and liked people. However, this combination could produce

extremely sensitive independent puppies, exactly the opposite of the desired result.

The breeder could, by testing the puppies determine which characteristics each puppy

had inherited and then breed only from the puppies possessing the desired combination.

REFERENCES

Campbell, William E., Behavior Problems in Dogs (American Veterinary Publications, 1975)

Fox, Dr. Michael W., Understanding Your Dog (Conard, McCann, Geoghegan, 1972)

Gibbs, Margaret, Kennel Dog to House Pet: Looking at Kennel Dog Syndrome

(Purebred Dogs AKC Gazette) January 1978, p.p. 24-33

Humphrey, Elliot & Waner, Lucien, Working Dogs, National Press, 1974

(First published in 1934)

Pfaffenberger, Clarence J., The New Knowledge of Dog Behavior (Howell, 1963)

Scott, Dr. John Paul & Fuller, Dr. John L., Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog (University of Chicago Press, 1965)

Trumbler, Eberhard, Your Dog & You (Seabury Press, 1973)